With university staff and students dispersed around the country, every day starts with a roll call to stay in touch and support each other

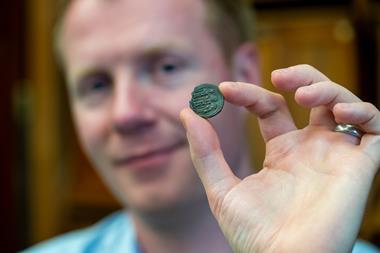

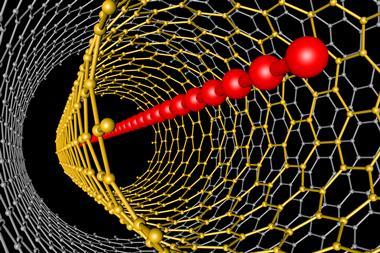

Viktoriia Moskvina is a senior research fellow at Taras Shevchenko Kyiv National University (KNU), researching compounds that could be used as building blocks in the synthesis of new drugs or functional materials. She was in Kyiv on 24 February but left shortly afterward and is currently working remotely in Lviv.

I still feel like we are living one day at a time. I learned that the war had been declared from my husband at 5am on 24 February. He had insomnia, and when he woke up and learned about it, he said, ‘well, it has begun’. I couldn’t believe it until I heard the air raid sirens.

My first thought was that we needed to take our 9-year-old son somewhere safe. We decided to go to western Ukraine. Every day starts with a roll call of colleagues, students, PhD students. We keep in touch. Some students write, ‘please, talk to us; we are too worried about our relatives’. Lots of students didn’t go home but gathered somewhere in Lviv, Chernivtsi, or Ivano-Frankivsk regions. They are in this strange situation on their own. So we are trying to support them.

In the very beginning, I was volunteering, helping to connect people with each other, finding them accommodation through friends of friends, helping organise the evacuation of relatives from ‘hot spots’ in Kharkiv or around Kyiv. In the first two weeks people were collecting medicines in Lviv and then transferring through Vinnytsia to Kyiv. Now there are loads of very experienced people engaged in such activities, so my help there is not needed anymore, and I switched to scientific volunteering.

I am the head of the Council of Young Scientists at KNU, and I am also on the board of the Council of Young Scientists at the Ministry of Education and Science in Ukraine. I carried out a countrywide poll for scientists asking what they need right now to keep working. 90% of participants said they need access to scientific databases and to the literature.

My first thought was that we needed to take our son somewhere safe

We submitted some publications before the war and now are working on getting them ready for print. Right now we cannot perform any experimental work, but there is a lot of previous data we need to analyse that could be made into publications. Two years of coronavirus and remote work with limited access to the equipment has taught us to save our data to the cloud and to keep lab notebooks online. But if, God forbid, this war drags on, it will be difficult since the data left to analyse will be depleted sooner or later.

In the future, we will need help to rebuild the laboratories. Perhaps some equipment considered not modern enough to be used elsewhere could be sent as humanitarian aid. Lots of the equipment we are working with is pretty old already, and we don’t even have enough of that. Reagents would be a great help too, because they are very costly.

I got an invitation to a conference in St Petersburg; I was also suggested as a reviewer for a paper by Russian scientists. I refused. I believe that the work of Ukrainian chemists shouldn’t be sent for review to the aggressor country either. Unfortunately way too many Russians, even when not publicly supporting the war, just ignore it and think we can continue business as usual, as if their military weren’t destroying Ukrainian cities. Russia attacked Ukraine. This understanding must be there.

This article is based on an interview performed by Anastasia Klimash

Living through the war in Ukraine

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

Currently reading

Currently readingChemists in Ukraine: Viktoriia Moskvina

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

No comments yet